on having consumed two degrees

‘Education occurs in a social context, and it has social ends.’1

––

Let’s start with the harshest possible case:

‘I have only been allowed to progress as far as I have in academia, and to “attain” first-class grades, because none of my work has ever constituted anything beyond, ultimately, an act of consumption. The university won the moment I paid the tuition, the rest was theatre. The threshold of substantive, consequential research was never breached.

The “decisions” we, as humanities Bachelors/Masters, made as to which essays to write and which to not, which avenues of academic inquiry to pursue and which to not, were arbitrary; they existed wholly within the bounds of a purchasing decision already ensured.’

Can this really be true? In the interest of interrogating and hopefully unpicking this claim, the first question seems to be:

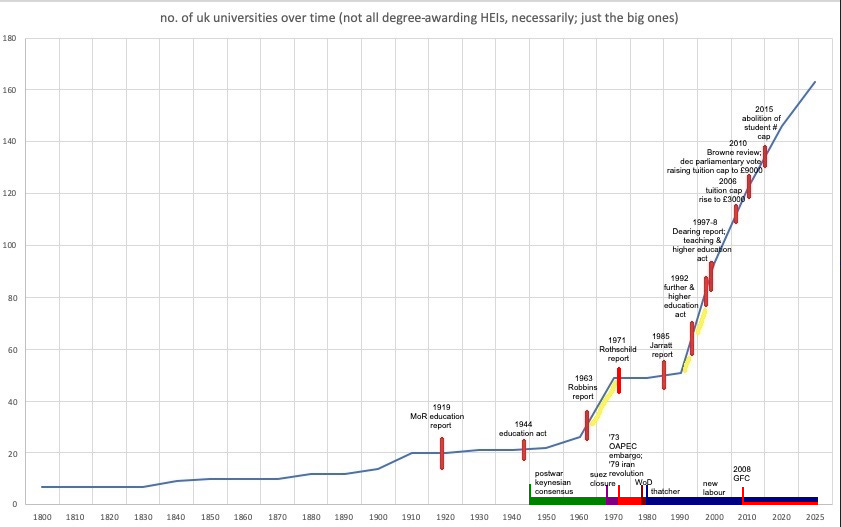

what the fuck happened to UK universities?: a concise history of the marketisation of higher education 1985-present

pre-1985

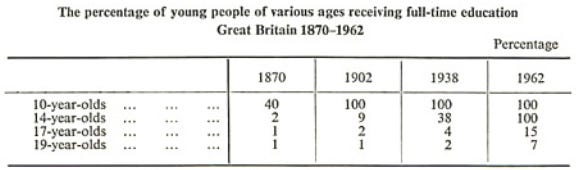

The twentieth century had seen a steady rise in demand for and provision of secondary education: Educations Acts of 19182 and 19443 raised the mandatory school leaving age from 12 to 14 and 15 respectively, and abolished fees first for state elementaries and then for all secondary schooling.

The ‘44 Act also mandated that ‘further’ education should be made available ‘for any persons over compulsory school age who are able and willing to profit by the facilities provided for that purpose’.

By this point, there were only 22 university institutions in the UK: the 7 that reigned from the 13th-19th centuries (just Oxbridge in England), the 19th-century additions (University of London colleges etc.), and the early 20th-century ‘red-brick’ or ‘civic’ universities which were previously technical colleges – medical/engineering – but were granted independent degree-awarding powers, saving the students having to travel to UoL for external examination.4

So, in this context of a rising level of secondary-education among the population and limited universities, what was ‘further’ education considered to be for?

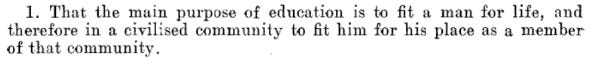

In 1919 the ‘Ministry of Reconstruction’ following WWI appointed an ‘Adult Education Committee’ to write a report on the status of, and recommendations for, post-secondary schooling. Addressed to the Prime Minister, the report argued that in order for Britain and its European allies to reckon with postwar issues of social, economic, and political concern – state ownership, state intervention in trade, party political structure, women’s liberation, employer-labour relations etc. – an educated populace was necessary. (‘Is it not manifest that a democracy which has to solve these questions must be an educated democracy?’)5 The report then described explicitly what it saw as the ‘main purpose’ of education:

‘The goal of all education must be citizenship’; ‘the essence of democracy [is] not passive but active participation by all in citizenship.’

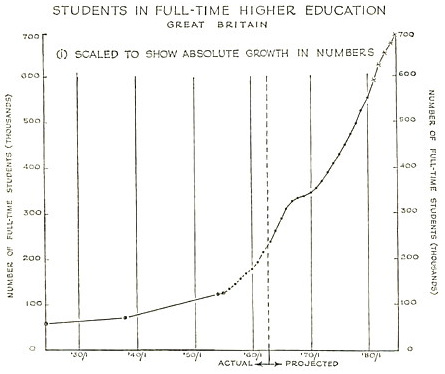

These themes were taken up in 1963 with the publication of the ‘Robbins Report’, a commissioned report from the Committee of Higher Education chaired by LSE economist Lionel Robbins. It is hard to overstate the influence of this 1963 report; all later higher-education reports/acts harken back to it, and seek by the comparison (largely disingenuously) to legitimise themselves. The Robbins Report frames itself as a response to the exponentially growing demand for university places: a projected 250% increase in student place-provision from 1962/3-1980/1 will ‘mark the dawn of a new era in British higher education’.6

Reiterating the ‘44 Education Act’s call for higher education for ‘any persons … able and willing’ to benefit from it, the Robbins Report begins from an ideological commitment to providing higher education for ‘all who are qualified’:

In order to meet increased demand, the report recommends an ‘expansion’ of the higher education sector (resulting in both the construction of ‘plate glass’ universities and the granting of degree-awarding powers to ‘Colleges of Advanced Technology’, doubling the total number of university institutions from 22 to 45 during the ‘60s), as well as bringing all universities, technical/commercial/art colleges and teacher-training colleges into one ‘system’. Having been allowed to germinate independently, all higher education providers must form a ‘decentralised initiative … inspired by common principles’. The report defines these four ‘common principles’ as:

The ‘instruction in skills’ for the ‘general division of labour’.

The ‘promotion [of] the general powers of the mind’; ‘to produce not mere specialists but rather cultivated men and women.’

The ‘essential search for truth’.

The ‘transmission of a common culture and common standards of citizenship’; providing ‘equal opportunity’ for cultural participation by ‘compensat[ing] for inequalities of home background’.

The ultimate end of higher education, the report contends, is to develop ‘man’s capacity to understand, to contemplate and to create’; to enable its ‘citizens to become not merely good producers but also good men and women’.

Perhaps the most interesting section of the Robbins Report comes in its fourteenth chapter, where an extended argument is made against the notion of education as economic investment. The argument begins by considering the analogy between education and ‘commercial measurements on private investments’: a budding lawyer, for example, may ‘contrast the expense over the years of training with the probable yield estimated in terms of average income in that profession for an average expectation of life’, in the same manner one invests in ‘coal or electricity’. Beyond the problem of relative remuneration – the ‘return on investment’ (ROI) calculated in terms of the ‘yield’ of an increased lifetime salary – differing between disciplines and times and places, the analogy runs into a more ‘fundamental difficulty’:

‘Education … creates the milieu in which the day-to-day calculus of the price system has to operate.’ In other words: the lifetime-salary ROI of different educations is subject to capital, and what ‘the market’ (the collection of individual producers/consumers and institutions which comprise the circulation of capital) deems to be socially or economically productive work – a value judgement for which education is necessary. The report goes on:

Education, far from a commercial investment to be calculated against the likely ‘yield’ of an increased lifetime salary, is the investing of a student with a ‘capacity for systematic invention’; it is the creation of a ‘versatile community, apt to mutual stimulation of invention and understanding’. The report claims that even if it were possible to calculate the exact pecuniary ROI of any given degree, to call this figure the ‘return’ of the degree would constitute a category error. It’s not about the money you make: it’s about understanding what money is and how it functions; it’s about applying these ideas to generate new understandings of how money ought to be spent. It is, put simply, the creation of active citizens, reflecting critically on societal structures, participating in culture. For this reason, the report concludes:

The government of a healthy nation can never dedicate too much public money to higher education.

changing economic conditions

The Robbins Report was native to its particular socio-economic period. The 20 years following WWII saw broad adherence to the Keynesian principle of governmental fiscal stimulus increasing aggregate demand in the economy. (A simple chain reaction: budget-deficit spending (government invests in industry and public services on borrowed money) → employment increases → wage income increases → consumption increases → industry/business grows → wages increase further → government pays off its original debt via high taxation.)7 The postwar years – colloquially known as capitalism’s ‘golden age’ – worked for several reasons: low unemployment and high demand; an established welfare state (NHS and social security programmes) reducing economic uncertainty by providing secure living standards; a centrally-planned wartime manufacturing base to repurpose and build from; nationalised utilities and industry (rail, coal, steel, gas, electricity, aviation etc.); low interest rates (set by a newly nationalised Bank of England) incentivising borrowing-to-invest; and high income tax rates (95-99% for top earners). In this context, wherein government and people seem to be mutually involved in the creation of a better quality of life for all, it is easy to see how a notion of higher education as producing ‘cultivated citizens’ might emerge.

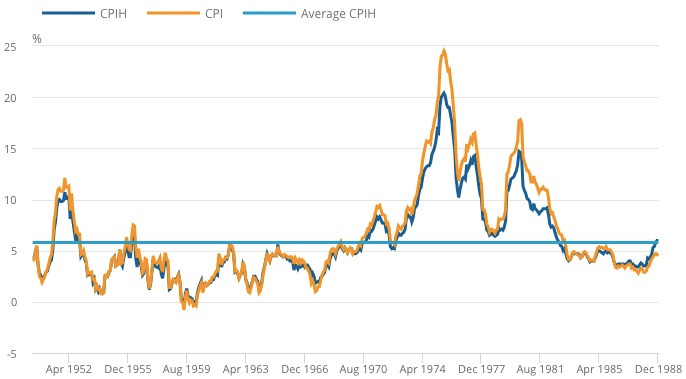

Stark changes from the mid-1960s onwards precipitated the implosion of this Keynesian order, a full explication of which lies beyond the scope of this higher-education thread. Suffice it to say: the UK economy has never existed in a vacuum. After a hard-fought 19th-century contestation between British capitalists and British labourers – the former incentivised to exploit the worker optimally, the latter pushing back against the six-16hr/day work week8 – British industry was forced to move production abroad where colonial subjects could be squeezed with greater impunity; in this way, as Jason Hickel articulates, ‘capital accumulation in the West is coterminous with the European colonial project’.9 ‘Economic growth’ – measured by the already spurious GDP metric – in Britain has long been contingent upon the exploitation of colonised nations, extracting cheap labour and natural resources from them by force. The first decade after WWII saw a sprawling wave of decolonial struggle: from the 1947 Indian partition, to the 1952- Kenyan Mau-Mau rebellion, to Iran wresting national control of their oil from the British ‘Anglo-Iranian Oil Company’ (AIOC) in 1951, to Egypt’s revolution and closing of the Suez Canal from 1952-6 (among many others), culminating in the 1955 Bandung Conference in Indonesia, attended by 29 core so-called ‘Third World’ states.10 Indeed, writing at the end of the Algerian National Liberation Front’s eight-year war against French colonial forces for independence, Frantz Fanon observed in 1961:11

In 1967, Israel – established in 1948 with the violent displacement of 700,000 indigenous Palestinians, to operate as a primarily US- and British-backed proxy in the Arab region shoring up Western economic interests12 – bombed Egyptian airfields after having invaded the then-Jordanian-ruled West Bank, instigating a ‘Six-Day War’ with an Arab coalition of Egypt, Syria and Jordan. Egypt, during the course of the aggression, closed the Suez Canal – through which 25% of British oil consumption flowed – until 1975. In 1973, Egypt and Syria launched an offensive to reclaim territories Israel had occupied during the ‘67 Six-Day War, and then-US-president Nixon ordered $2.2billion of emergency aid be sent to Israel. Two weeks later, the Organisation of Arab Petroleum-Exporting Countries (OAPEC), led by Libya and Saudi Arabia, announced a retaliatory oil embargo, reducing their oil output by 25%.13

The 1973 Oil ‘Shock’ (the resultant supply-side price increase from a pan-Arab resistance to Western-colonial extractivism in the region) was, in its effects on the British economy, hugely exacerbated by the 1971 ‘Nixon Shock’. Due to foreign aid, foreign investment and military spending, by the 1970s there were too many dollars in global circulation to be conceivably backed up by US federal gold reserves. (Since the ‘Bretton Woods’ conference in 1944, US dollars had been guaranteed by gold at $35/oz, and world currencies were ‘pegged’ to the dollar at fixed exchange rates.) Countries began frantically exchanging their overvalued dollars for US gold en masse in a ‘run’ on the currency, and the US Treasury predicted gold reserves would be depleted completely in less than a decade. Nixon therefore, in August 1971, decoupled the dollar from its gold value – ‘floating’ the currency – and effectively abolished the Bretton Woods system.14 The pound, while still pegged to the dollar in 1967, was devalued 14% in an attempted stabilisation,15 but was also allowed to float by 1972.16 When the ‘73 Oil Shock hit, then, it caused a catastrophic inflationary crisis.

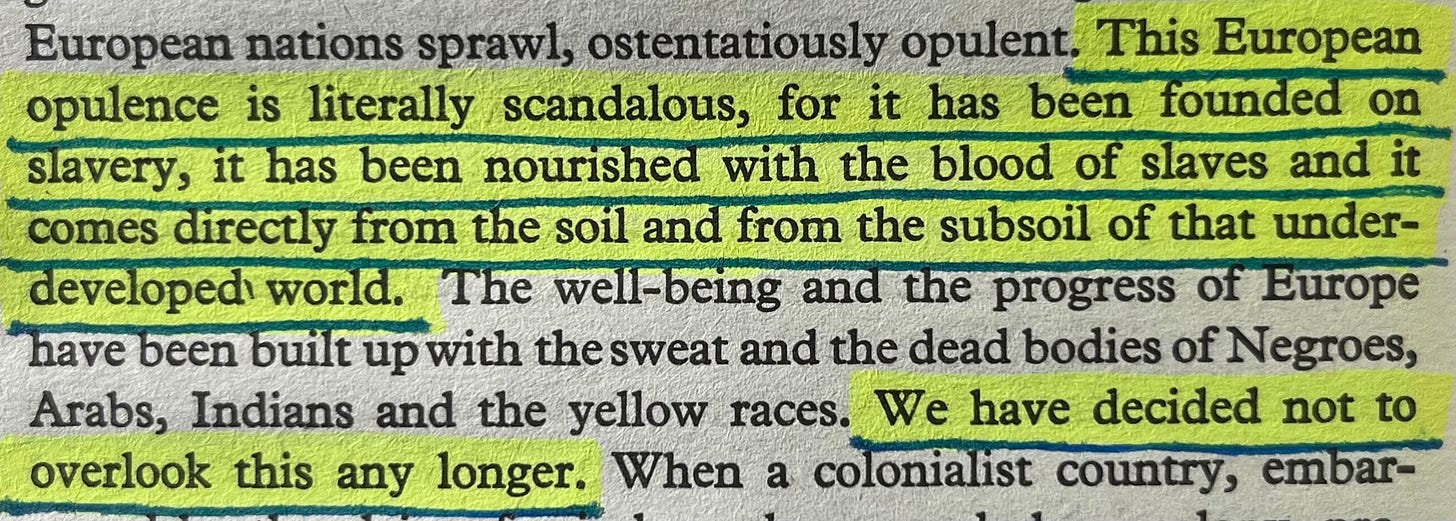

With global currencies floating only relative to each other, decoupled from the value of any ‘money commodity’,17 oil prices skyrocketed by almost 400%, from $2.90/barrel to $11.65/barrel by January 1974.18 UK Consumer Price Inflation had been rising since the Suez closure of ‘67, but exploded over ‘73-75 from 8.8% to 25%.19

(Almost back to universities.)

The nature of the crisis afflicting the UK in particular was an unprecedented dual-phenomenon of ‘stagflation’ – i.e. of simultaneous stagnating economic demand and commodity price inflation – characterised by a fall in GDP, rising unemployment, and decreased investment/expenditure. How did UK governments respond to this crisis? The first attempt, made by then-Conservative-chancellor Anthony Barber in 1972, was to immediately grow the economy by cutting income tax, replacing the 33% ‘luxury purchasing tax’ with a mere 10% levy on ‘non-essential’ goods, and deregulating finance. This attempt at flooding consumers’ pockets with cash and hoping it immediately spiked GDP to outpace inflation, in fact, ‘overheated’ the economy – aggregate supply couldn’t keep up with aggregate demand – and prices simply rose to match increased consumer spending power, which in turn further raised prices etc. (i.e. creating a ‘wage-price spiral’, worsening inflation).20

Barber’s ‘Dash for Growth’ flop ushered in Harold Wilson’s 1974 return as Labour prime minister – forming a minority government in February, before winning a slim three-seat majority in a second general election later the same year – on a ticket of socialist duct-taping: food subsidisation, rent freezes, pension increases, and asking trade union members, on account of these public quality-of-life interventions, to uphold their side of an informal ‘Social Contract’ by exercising ‘voluntary wage restraint’. These policies were to be funded by increases in income tax, top-rate investment tax, employers’ national insurance contributions, and further borrowing.

These measures proved, in the face of inflation inexorably soaring to 25%, ineffective. By late 1974, Treasury officials declared that the economy had insufficiently grown, that the ‘Social Contract’ had insufficiently tempered union wage demands, and that, as Vernon Bogdanor relates, ‘a new approach was needed’.21 Chancellor Denis Healey announced in budgets from April-July 1975 a series of ‘fundamental policy changes’: in an abandonment of the Keynesian commitment to full employment, a ‘voluntary income policy’ enacted a 2.5% real-terms income reduction for workers, social security programmes were fixed at cash limits (real-term reductions), and public expenditure was slashed across the board.22 It was a programme of stark austerity. In the first signs of ‘monetarism’ to come – i.e. removing money from the economy to combat inflation – public spending was cut further by November ‘75, and further still through April-July 1976.

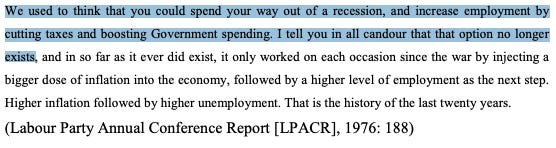

By the time James Callaghan took over from Wilson as Labour leader and PM in ‘76, the consecutive years of domestic inflation caught up with the pound’s nominal exchange value, depreciating 20% by September. In lay terms: other nations viewed the domestic British economy to be fucked, and so our currency was correspondingly fucked. Healey pleaded with the Washington-based International Monetary Fund (IMF) for a bailout, and $3.9billion came later that year, with strings attached. (Something of a precursor to the IMF’s ‘structural adjustment programmes’.) The IMF demanded that the UK cut its public spending by a further $7billion from 1977-79; Healey negotiated $2.5billion of cuts over the period. Callaghan made the following speech to Labour Conference on 28/09/76, just after Healey had announced the IMF loan, though, as Bogdanor observes, the speech ‘did no more than confirming for public consumption a policy shift that had already been made’:

This decisive break with Keynesianism and embrace of austerity – the switch of priority from employment to inflation, from spending to restriction – can be said to have set the stage for the economic order in whose long shadow, fifty years later, we’re still living. Indeed, to hear Andrew Murray, former chief of staff of Unite the Union, tell it:23

Thatcher was, though, already putting together a plan. Newly elected Conservative leader in opposition, she was meeting with staff from the Institute of Economic Affairs (IEA) and freshly established Adam Smith Institute thinktanks – along with lead writers from both The Times and the Daily Telegraph – every Saturday to ‘plan strategy [and] co-ordinate activities’ to make the group ‘more effective collectively’.24 Having reportedly slammed Friedrich Hayek’s Constitution of Liberty on the table at the beginning of her leadership and exclaimed ‘This is what we believe!’,25 Thatcher was an ideological devotee of the ‘Austrian school’ of economics, which advocates for deregulation of markets (i.e. reduced governmental power; freedom for business), privatisation of public utilities/services (corporate incentives breed efficiency), and holds, moreover, that people are preeminently selfish individuals who best exercise their ‘freedom’ through consumption choices in the marketplace.26 A completely unfettered world governed by market incentives alone, the school contends, begets a ‘spontaneous order’.27

By the Iranian revolution at the start of 1978 – the climactic backlash against the AIOC, reducing global oil supply by 4% and causing a second UK inflationary wave – Callaghan’s government was both committed to austerity and bound by the IMF. All price controls from the ‘74 socialist mandate had been abolished, and harsh wage caps sprung a series of public and private strikes. Labour antagonised the unions, ripped itself apart from the inside, and after the Winter of Discontent the conditions were in place for Thatcher’s Tories to walk the May 1979 election.

1985

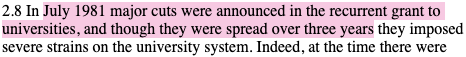

Into this vastly different climate comes the next significant higher education report: the Jarratt Report. Commissioned by the Committee of Vice-Chancellors and Principles, this report immediately positions itself in reaction to swathes of funding cuts imposed on the sector since 1981:28

Recurrent University Grants Committee (UGC) teaching grants – the bulk of universities’ public funding before research-specific grants from research councils – were slashed by, on average, 17% across all higher education institutions, and provisions were made for faculty downsizing:

The report makes clear that by 1984, at the outset of Thatcher’s second term, universities were being told that UGC funding will continue to fall in real terms – i.e. ‘less than level’ with the rate of inflation – and that universities ‘would be expected to compensate for [these cuts] by increased efficiency’:

Indeed, UGC funding was projected to fall 2% in real terms per annum from 1985-88. The Jarratt Report therefore intervenes as ‘an efficiency study of the management of universities’, primarily concerned with ‘ensuring … that optimum value is obtained from the use of [university] resources’. It is in this framework that we find the first reference to students as ‘customers’:

The report claims that the very conception of what a university is, the conception outlined in the Robbins Report which accompanied sector expansion through the ‘60s, is outmoded, and must be refigured in light of budgetary restrictions:

To this end, universities will have to engage in ‘strategic planning’ processes ordinarily native to ‘other organisations’ – namely, ‘corporate strategic plans’. The report goes on to criticise existing sector-wide procedures and recommend corporate ameliorations. To start, the report criticises the lack of a ‘merit-based’ system of resource allocation within and across universities:

The solution, drawn up the following year in 1986, would be the ‘Research Assessment Exercise’ (a precursor to the current ‘Research Excellence Framework’ (REF)), a five-yearly ‘research quality’ evaluation of – and within – each institution, marking research ‘output’ based on a set of standardised criteria. Universities and their departments were, for the first time, made to, in effect, compete for their public funding. Concurrently, the report states the following:

This is a monumental distinction. The report here advises that rather than ‘refilling vacant posts’ – that is, respecting the existence of faculty positions and finding new scholars to fulfil their established function – all university ‘resources’ (staff, materials, funding) can and should be reduced to ‘cash’. All elements of a university are therefore reduced to numbers on a balance sheet to be organised ‘efficiently’, so as to to be ‘optimally deployed’ to generate maximal ‘value’.

All university institutions – represented in this new schema preeminently as their financial accounts – should be made ‘formally consistent’. Departments are refigured as ‘budgetary units’; students are reduced to notional units of ‘income’ and all academic functions – that is, teaching, research, accommodation – are ‘overheads’; administrative staff at each university reformulate all activity into reports/statements to ‘serve’ a central financial-academic committee’s ‘merit-based’ resource-allocation process (the REF, and its later teaching equivalent, the TEF). The university becomes, principally, something to be ‘managed’. It is a corporate entity with corporate priorities: ‘efficiency’, standardised metrics of ‘performance’, and its ‘customers’.

A final trend the Jarratt Report notes, in reaction to UGC cuts, is:

The UGC’s official recommendation to universities to cope with decreased recurrent-grant money, and to maximise ‘efficient’ use of their constrained resources, was to reduce student number targets by an average of 5%. At this stage, the UGC was obliged to provide universities a flat per-head ‘fee’ to fund each student’s tuition, and so, naturally, what universities instead did was increase student intake to offset the shortfall in teaching-grant money (already a shift in priorities was emerging from block grants to student-fee-contingent ‘income’). An additional coping measure was to lean on an increasing amount of donated funds from alumni, private individuals, or industry partners. All of which takes us neatly into:

the ‘90s

If the goal of the Jarratt Report was to, within the bounds of 20-25% grant-spending cuts from Thatcher’s government, corporatise the university in a quasi-market of competing institutions to ensure students received ‘value for money’, what was this ‘value’?

Two things happened in the ‘90s: first was the 1992 Further and Higher Education Act that incorporated 38 ‘polytechnics’ into the university system, which, alongside five new institutions, almost – again – doubled the total UK university count from 46 to 89 by 1994.29

Second was the publication of the 1997 Dearing Report and its adjoined 1998 Teaching and Higher Education Act: it is these that complete the substrate of our current system, which, as will be seen, has developed largely unrestrainedly from the report’s principles.

The Dearing Report – headed by University of Nottingham chancellor Ronald Dearing and conducted by the National Committee of Inquiry into Higher Education – like the Jarratt Report before it, begins by framing itself in reaction to sustained cuts in public funding:30

In conjunction with this halving of public funding over 25 years, the report echoes Jarratt et al.’s conception of the university as a principally corporate entity competing in an ‘education market’ – though now draped in the internationalist language of globalisation favoured by Tony Blair’s freshly elected ‘New Labour’ government:

The ‘92 expansion of the university sector – the incorporation of polytechnics – is framed by the report, in this light, as providing a ‘level playing field’ on which these corporate-universities could ‘compete for students’:

Within this by now familiar schema, the report clarifies what it sees as the point of a university education, and where a degree’s ‘value’ lies. A description is provided of ‘the central role of higher education in the economy’:

This is, I think, something of a smoking gun. ‘To be a successful nation in a competitive world … we must invest in education to develop our greatest resource: our people.’ The report goes on to be a little more explicit:

In an era of globalised capital, ‘the only stable source of competitive advantage … is a nation’s people’. The sleight of hand is subtle, but gets at the essence of this report: despite glib references to the intrinsic value of ‘lifelong learning’, Dearing at al. repeatedly subordinate this learning to the production of competitive labourers in a global labour market. That is, a degree is ‘valuable’ insofar as it enables a student to enter this job market, governments are incentivised to fund the higher education sector insofar as it gives the UK’s labour supply an international competitive edge, and students, from their perspective, are beneficiaries of higher education insofar as their degrees – as standardised, transferrable units of ‘knowledge’ – translate into enhanced employability.

The provision of ‘learning programmes’ is, at every point, figured transactionally. There are four major players: government, universities, students, and industry. Universities are, foremost, ‘knowledge-producers’; they are the vendor of standardised, universally recognised units of ‘knowledge’. Students, by attending universities, are assured that they, by the acquisition of this ‘knowledge’, are imbued with a desirability or advantage within a competitive labour market. Industry profits from a labour market increasingly comprised of ‘knowledge-havers’; a prospective employee with a record of acquired knowledge-units is eminently employable. Finally, governments profit by – in the words of the report – becoming ‘economically successful nations in a competitive world’. It is a transactional network in which ‘knowledge’ is subordinated to capital. Indeed, the creation of what the report calls a ‘Learning Society’ is imperative for, above all, the needs of the economy:

The report ultimately goes on to claim that, of the four ‘stakeholders’ in the university system, students – due to the ‘labour market benefits’ (employability + an 11-14% lifetime salary increase) – are the system’s greatest beneficiaries:

And that, therefore, with their ‘improved employment prospects and pay’, students, during this period of receding public higher-education funding, ‘should make a greater contribution to the costs’.

Various measures for introducing this ‘cost-share’ are considered: a graduate tax, figured as an ‘income tax supplement’ and favoured for its simple implementation, high revenue generation, and its ‘natural income contingency’ (with the opportunity to be made ‘more progressive than income tax itself if desired’), is ultimately disregarded on account of potentially being punitive to high earners. A ‘deferred contribution’ option is considered, whereby a graduate would make capped, interest-free contributions as a proportion of income over a predetermined number of years, but is vetoed on account of not generating any immediate-term revenue for the sector. Finally, a scheme is settled upon: ‘Contributions supported by loans.’

On the basis of Dearing et al.’s recommendations, New Labour, via the 1998 Teaching and Higher Education Act, introduced a £1000/yr tuition fee for students with household family incomes of ≥£35k/yr, to be paid back via general taxation until the age of 65; students with household family incomes ≤23k/yr were exempted from the fee, with a sliding percentage scale between these bounds.31

Students were, for the first time, paying for higher education.

browne review – present

From 1998-onwards, the ‘share of the cost’ of higher education borne by students themselves only grew. By 1999/2000, public maintenance grants for living costs were replaced with loans repaid at 9% of graduates’ income in excess of £10k/yr; by 2004, a new Higher Education Act permitted universities to charge variable tuition fees up to £3000/yr;32 by 2009/10 this cap had risen with inflation to £3225/yr.

In November 2009 Peter Mandelson – Business Secretary under Gordon Brown – commissioned a review of higher education funding to be headed up by Lord Edmund Browne (BP CEO 1995-2007). The resultant report, the Browne Review, was published in October 2010, and student fees factored heavily into the general election debates of that year.33 Nick Clegg, leader of the Liberal Democrats and ultimate coalition-victor alongside David Cameron’s Conservatives, pledged in December 2009 to ‘scrapping’ tuition fees altogether:34

The Browne Review includes all of what are, by this point, the greatest hits. Higher education is necessary because it enhances individuals’ employability; higher education is necessary because it increases individuals’ lifetime salaries; higher education is necessary because it promotes GDP growth:

The Browne Review is more explicit on these points than the Dearing Report dared to be: ‘knowledge’, here, is referred to – in the interest of private profit ‘capture’ – as itself a form of capital good in which firms invest:

And the pecuniary ROI of a degree – that is, the lifetime salary increase – is quantified in 2010 as a £100,000 bump:

The review therefore identifies the higher education sector as a high-growth, high-return investment opportunity:

Browne et al. provide recommendations to the government on the basis of increasing ‘competition for students between HEIs’, and thereby securing financial stability for universities ‘that are able to convince students that [their degrees are] worthwhile’.

The review first recommends a 10% increase in student place provision across the sector:

And then recommends that the £3225/yr cap on tuition fees be lifted, and replaced with a system whereby higher education institutions are levied on all income from tuition charged above £6000/yr:

Under this proposed system, uncapped tuition loans would be repaid above an increased graduate earnings threshold of £21k/yr, accruing interest above that threshold at a rate of 2.2% + inflation, and would be written off after a period of 30 years:

These proposals were designed to supercharge the marketisation of the sector, both increasing the pool of students from which to generate ‘income’ and for this ‘income’ per head to be limited only by the number of students a given university was able to attract.

In December 2010 a Parliamentary vote on, contrary to Browne at al.’s recommendations, simply raising the existing tuition fee cap to £9000/yr passed with 323 votes in favour to 302 against.35 Nick Clegg, in violation of his pledge, voted for the motion, later apologising and decimating LibDem support for a decade.36 The Browne Review’s other points – on interest and the 30-year write-off period – were implemented, and the fee cap rose to £9250/yr by 2017 with inflation.37

In 2015, in the most recent significant step of the overall ‘liberalisation of UK higher education’, student number controls – that is, caps on student place provision across the sector – were abolished altogether.38 Tory Chancellor George Osborne justified the policy on the basis of 1) GDP growth:

and 2) pressurising competition between universities:

the 2020s funding picture

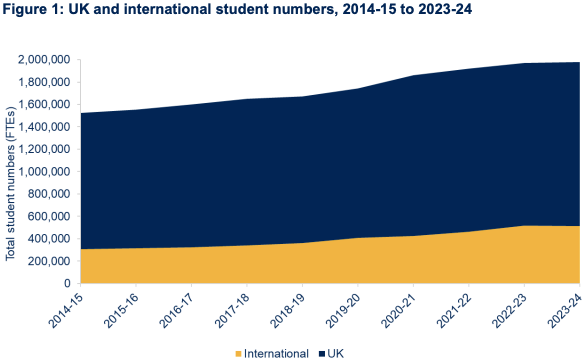

As per Office for Students (OfS)’s latest ‘Financial Sustainability of Higher Education’ report, full-time student levels – both domestic and international intakes – have steadily risen since the 2015 abolition of student number controls.39 (Note that the ‘63 Robbins Report started calling for expansion of the sector once this figure hit 200,000; by 2025 it’s approaching 2,000,000. The total number of UK universities has over this time risen from 22 to almost 170.)

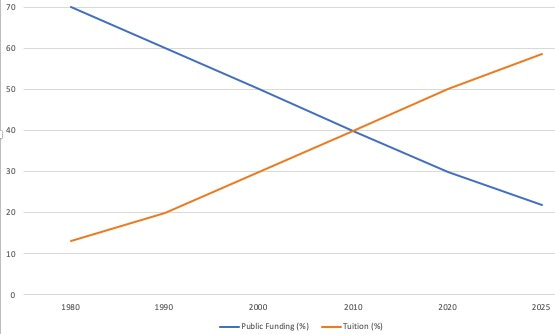

In 1985, the Jarratt Report’s figures showed that 64% of university funding came from UGC recurrent grants, a further 6% from research council grants, and 13% from tuition fees (a cost which, of course, was then also being borne by government). That’s 70% of university funding coming from teaching/research grants before tuition fees were even factored in.40

OfS figures show that from just 2020/21-2025/26, the proportion of public funding a university receives has, on averaged, decreased from 25.5% (11% from recurrent grants, 14.5% from research grants) to just 21.8% (8%, 13.8% respectively). Over the same years, funding from tuition fees – now borne by the students – has increased from 56% to 58.5%.41 If the trends since 1985 aren’t clear enough, public funding and private tuition loans are negatively correlated:

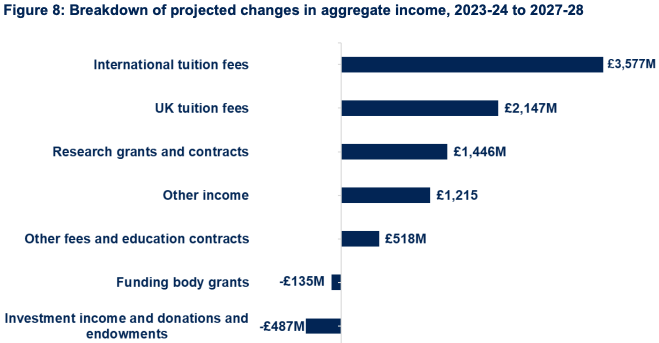

This means that, by design, the university sector has become increasingly reliant for its ‘financial stability’ upon student income (as ideologically espoused by the Browne Review). The 2025 OfS report indicates that the proportion of public funding will only continue to shrink, and the proportion of private tuition ‘income’ will only grow:42

Universities have been, via REF and TEF evaluations within an increasingly large sector, forced to compete for decidedly scant public funding, and are, with student numbers allowed to grow, now forced to compete for tuition income. The universities themselves, efficiently managed corporate entities, tout their wares by embedding their degrees in the labour market, pivoting from the ‘63 Robbins Report’s idealism of ‘essential truth’ and ‘citizenship’ to the cynical pecuniary return it decried (pay to learn; ‘learn to earn’; weigh the cost of a £9250/yr loan accruing interest over 30 years against a purported £100,000 lifetime salary bump). Market forces permeate the sector, and ‘knowledge-production’ is incorporated into enterprise which remoulds education in its image. The 40-year picture becomes clear.

what the fuck do I care?: the effects of marketising forces on universities and the rise of the student-consumer

Are universities structured in such a way as to produce people who care – truly – about anything? Is that, in 2025, their natural ‘output’?

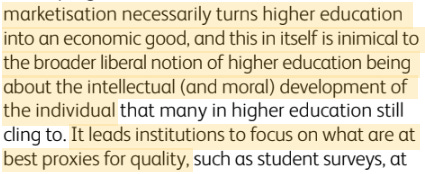

Roger Brown, former chancellor of Southampton Solent University and Chief Executive of the Higher Education Quality Council, identified by 2014 that market forces ‘turn education into an economic good’ by shifting university priorities towards ‘what are at best proxies for quality’.43 It’s worth unpacking the implications of this.

As mentioned above, from 1986 – as per the recommendations of the Jarratt Report – a number of assessment criteria were devised in order to allocate public funding to university institutions based on research (and later teaching) ‘excellence’. The first Research Assessment Exercises (1986-2008) graded up to four ‘units of assessment’ – i.e. articles/papers/studies published over the five-year assessment period – from each faculty staff member, and graded each ‘unit’ on a 1-5* scale, marking ‘originality, significance, and rigour’. Its successor, the REF (2008-), retained this assessment process and added one further metric of ‘excellence’: ‘impact’, defined as ‘an effect on, change or benefit to the economy, society, culture, public policy or services, health, the environment or quality of life, beyond academia’. Cris Shore and Susan Wright, in their article ‘Privatising the Public University’, observe the evolution of these means of assessment:44

The TEF (2017-) makes similar attempts to quantify ‘excellence’ of teaching with reference to metrics such as dropout rates, student satisfaction survey results, and graduate employment rates. The REF/TEF assessment regimes give rise to what Shore and Wright dub ‘audit culture’, and, it is emphasised, these audits by no means measure performance ‘passively’:

‘When a measurement becomes a target, institutional environments are restructured so that they focus their resources and activities primarily on what “counts” to funders and governors.’ That is, from the moment of REF/TEF’s implementation, the university institution is transmogrified into an entity which, above all else, serves to meet those criteria. As Yale/LSE anthropology professor David Graeber articulates, what is ‘excellent’ becomes what is ‘excellent’ on the assessment sheet; reality, for the institution, is subordinated to the metrics by which it is judged:45

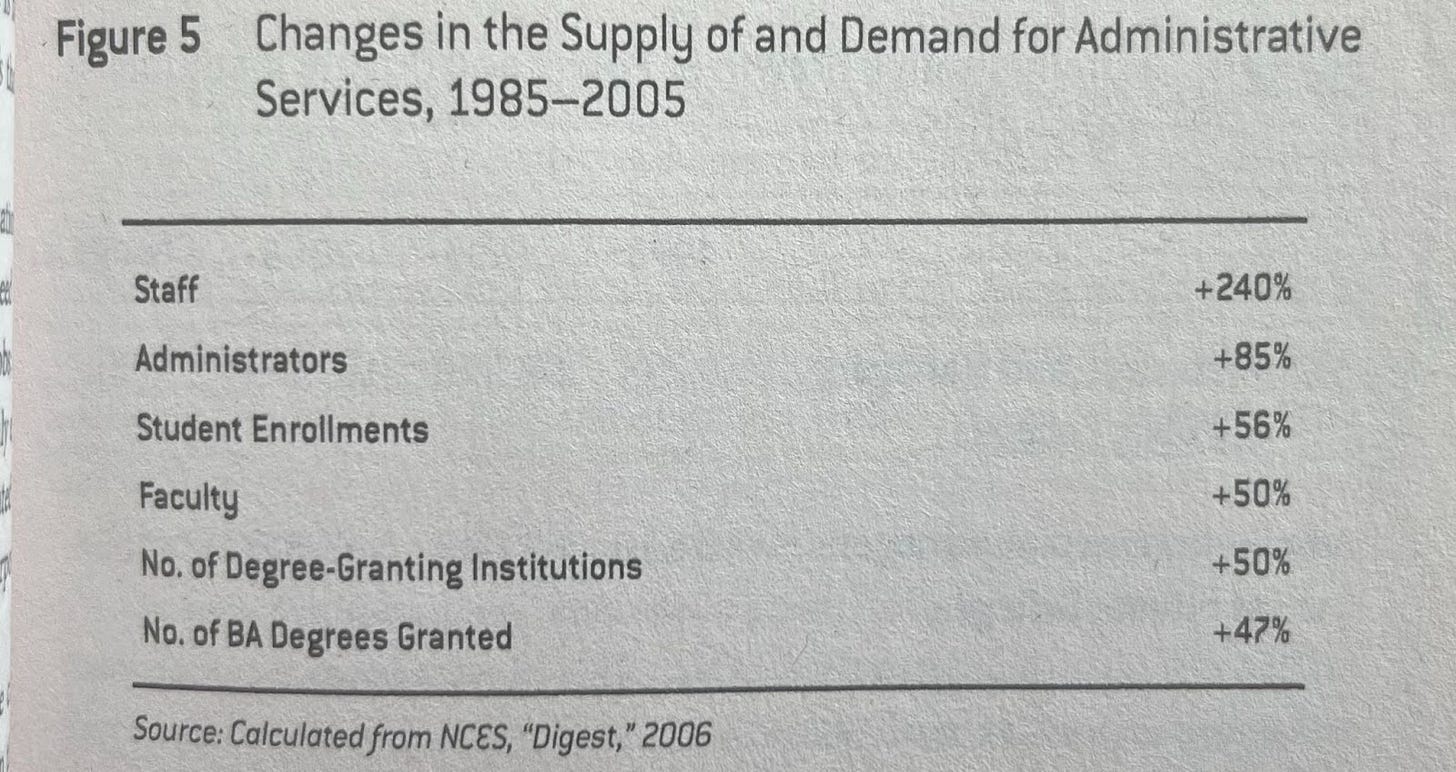

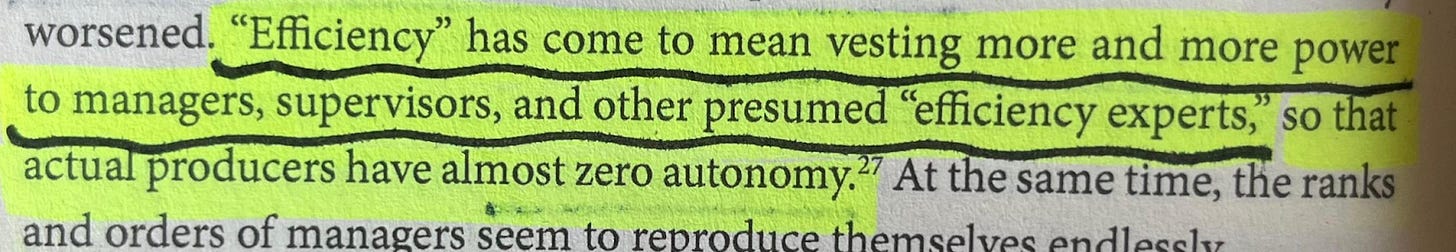

So what does this transmogrification into the audit-successful institution look like? What does the competitive university – for whom excellent research is that which the REF deems to be excellent, and for whom excellent teaching is low dropout rates, high student-satisfaction results, and high graduate employment rates – become? Graeber notes that the corporatisation of universities in the ‘80s (ostensibly in an improvement of ‘efficiency’) resulted in the growth of administrative and managerial staff outpacing the growth of faculty staff by almost five times:

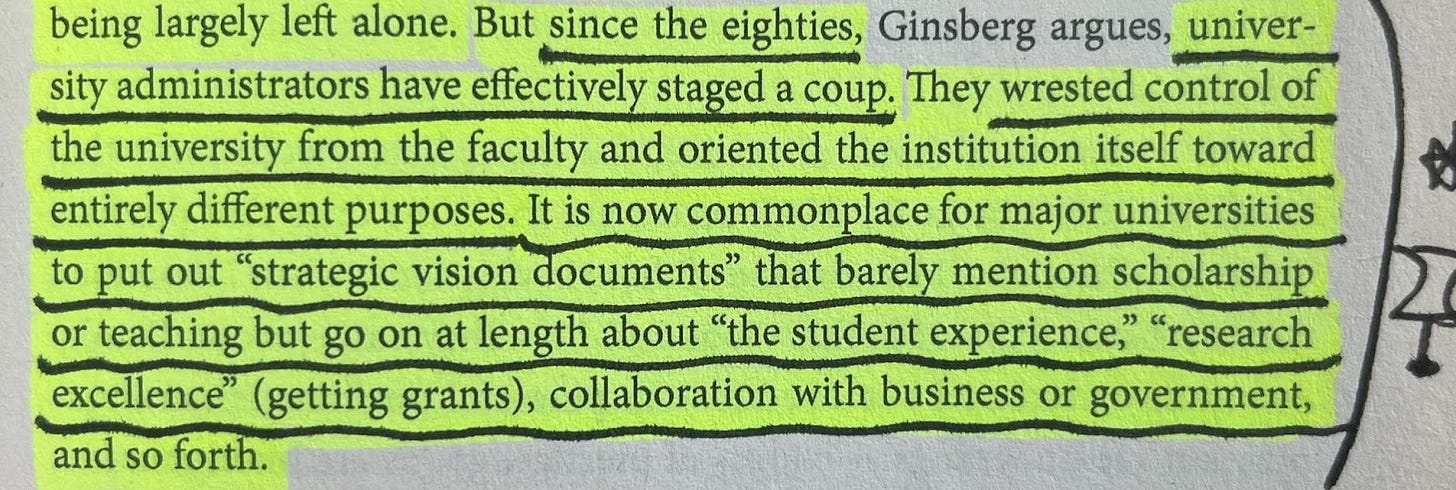

And that this displayed, in effect, an administrative ‘coup’:

Shore and Wright call this same phenomenon a rise of the ‘Administeriat’:

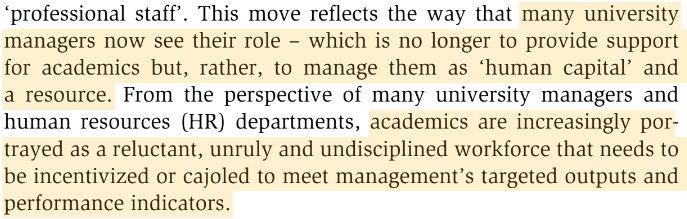

In line with the Jarratt Report’s ideal of reducing all university resources to ‘cash’, this ‘governing class’ of administrative staff see as their prerogative the management of faculty staff as ‘human capital’. Much of their role is to reduce every qualitative element of the university into terms suited to their management. See both Graeber and Shore and Wright:

These, as Brown put it, ‘proxies for quality’ end up alienating the entire institution from the reality of its educative service; the terms by which the university comes to understand itself are alienated from scholarship. As Dave Hitchcock, history professor at Canterbury Christ Church University, wrote in a piece from March 2025: ‘My students were a resource, and I was just a cost.’46

freedom means freedom to consume

What, from a student’s perspective, then, becomes the point of all this? The corporate university dedicates a large proportion of its budget to marketing/advertising, a fact to which any UK resident can attest. But the ads are notoriously unspecific; what exactly is the promise?

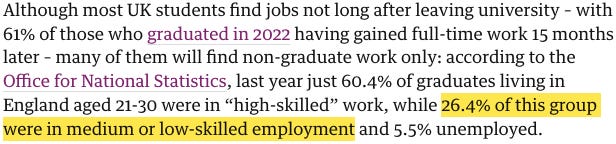

Julian Coman for the Guardian noted, again by 2014, that the pecuniary ROI of a university degree had already diffused across the popular consciousness.47 But by 2024, Jedidajah Otte demonstrated the complete dissolution of this ‘labour market benefit’ – ‘purchasing a degree as a stepping-stone to a job’ – ideal.48

Only 61% of 2022 graduates found full-time work within 15 months of graduation, at which point 26.4% found only non-graduate-level work and 5.5% remained unemployed. Within these 15 months and beyond, 50% of Otte’s respondent graduates had taken non-graduate hospitality, retail, administration, call-centre, supply-teaching or minimum-wage part-time positions. The entry-level job market has become saturated, with recruiters’ 2023 data showing an average of 86 applicants per vacancy. In this climate, respondents reported embarking upon postgraduate degrees ‘in desperation’, bereft of alternative options:

Why do students continue to make the purchase even when the terms on which the commodity – the degree, the standardised and transferrable ‘knowledge’ unit – is bought have proven demonstrably untrue? The answer lies in a paradox contained in Minister for Universities David Willetts’s 2013 address to Conservative party conference:

It’s immaterial that 44% of students in the 2024/5 cohort are expected to default on their tuition debt after the, now, 40-year pay-back period.49 It’s immaterial that degree certificates now provide no discernible advantage in the entry-level job market. Because, really, the pecuniary-ROI ‘transaction’ of a degree has always been, in the words of Shore and Wright, ‘largely illusory’.50 What matters is that the ‘forces of consumerism’ have been ‘unleashed’. An attitude that held, throughout the twentieth century, that the purpose of a university degree was to ‘fit a man for life’ – to produce ‘cultivated’, curious ‘citizens’ – was, in the ‘80s, usurped by an ideology which holds that freedom is an individual’s propensity to consume. Under the weight of legislative forces moulding the higher education sector into a quasi-marketplace, the content and experience of degrees themselves, submerged in alienating managerial terms and subjected to corporate standards of ‘performance’, were commensurately moulded into what a marketplace demands: commodities. These are the ‘high academic standards’ to which Willetts refers.

I think it’s true to say that, in a sense, the university does still produce ‘citizenship’. Attending university means being indoctrinated into societal norms of agency; how one engages with one’s university life is largely how one is expected to engage with the world beyond the institution. The university retains this disciplining force through norms encoded into its structure. What’s changed since the ‘63 Robbins Report is that the societal norm of agency which ‘citizenship’ entails, in a post-Thatcher world, is consumption at all costs. This what James Baldwin – speaking, incidentally, also in 1963 – meant when he said that ‘education occurs in a social context, and has social ends’; the means by which one is educated are subsumed into larger socio-economic structures, and educational institutions necessarily produce the sort of person native to those structures.

The vision of the IEA and Adam Smith Institute, with their US counterpart the billionaire-funded Heritage Foundation, in collaboration with news outlets like The Times and the Daily Telegraph, and brought to fruition under the Thatcher and Ronald Reagan premierships, was to produce an increasingly unregulated structure of corporate and individual-consumer freedom. Hayek’s student Milton Friedman – the most notorious communicator of the Austrian ‘free market’ tenet – spoke of ‘stepping straight in’ to the Labour tumult of the ‘70s, at the dawn of Thatcherism:51

The privatisation of public services, or, in the case of the UK higher education sector, morphing public services into quasi-markets with an increasing reliance on private funding, evidently mars those services. The myth of ‘business freedom is individual freedom’, or ‘wealth trickling down’ from the largest ‘value generators’, or remodelling public services in the name of ‘efficiency’, have all been empirically debunked. (See for examples from other sectors the latest Common Wealth report on the failures of privatisation.) And yet, students consume. From Mark Fisher’s metaphor of the neoliberal order as having ‘zombified’,52 to Abby Innes’s characterisation of neoliberal Britain as ‘late-Soviet’,53 there is a growing consensus of the ‘free market’ doctrine (Willetts’s ‘unleashing’ of the ‘forces of consumerism’) having been allowed to continue beyond its making any empirical sense.

a society rots from the head (a brief note on the particular plight of the humanities)

While all subjects have seen universal public spending cuts since the ‘80s, the post-Browne Review 2010 coalition government took a particular axe to the Arts and Humanities (A&Hs) and Social Sciences. Recurrent block teaching grants were, for the A&Hs, abolished by 2014:54

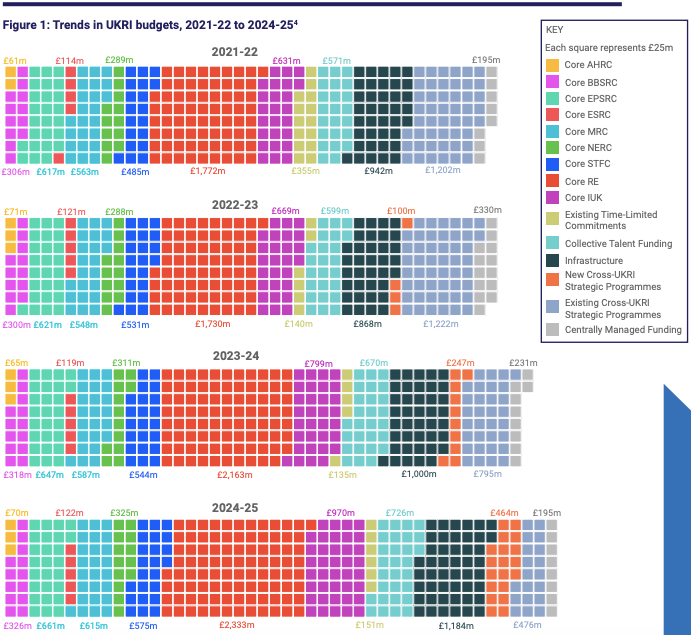

And data from UK Research and Innovation (UKRI; the centralised non-departmental governing body overseeing all research ‘committees’ (né ‘councils’)) shows that the Arts and Humanities Research Committee consistently receives 0.78%–0.79% of the overall UKRI annual budget, relative to STEM, medical, economic and social-science research committees which receive a combined 26%–27% of the budget:55

This minuscule research budget allocation is likely due to the categorical unsuitability of the humanities to the particular criteria of the REF.56 Cambridge medieval-philosophy fellow John Marenbon wrote in late 2018 that research assessors reviewing the four ‘units of assessment’ from each full-time faculty member are tasked, in A&Hs departments, with reading ‘the equivalent of a full-length book every day for nine months’. To get through this sheer load, a general rule of thumb – for ascertaining a grade of ‘excellence’ and ‘impact’ – is ‘10 minutes for a book, two minutes for an article’:57

And beyond this logistical difficulty, the nature of the department’s research ‘output’ itself is affected, as faculty are incentivised to produce work that is preeminently assessable:

Faculty are incentivised to avoid risk (research/written works that are not published within the five-year assessment period are ineligible for assessment), and to produce faster, digestible, ‘superficial’ articles. Moreover, the research undertaken must be conceivably relevant to the world ‘beyond academia’ – i.e. what research is considered ‘useful’, ‘effective’, or ‘beneficial’ is dictated to the academy by the external culture/economy, limiting academic freedom to pursue publicly counter-intuitive lines of inquiry – as ‘impact’ counts for 25% of the ‘excellency’ score:

So, due to the intrinsic inadequacy of the REF to determine the ‘value’ of humanities scholarship, the ostensibly meritocratic UKRI resource allocation underestimates the worth of A&Hs funding, feeding the associated research committee its 0.78-0.79% crumbs of the budget. This, combined with the abolition of recurrent grant funding, keeps A&Hs departments in a perennially emaciated state. No other branch of the higher education system, therefore, is so acutely exposed to market incentives, and the need to ‘convince’ prospective students to undertake their programmes in order to keep afloat.

But what is the social cost of economically/culturally undervaluing the A&Hs? I recently heard literary scholar Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak refer to the Humanities as having a ‘meta-vocational’ function.58 All subjects advance the frontier of human knowledge, but the Humanities, Spivak contends, in their particular epistemological role, tackle ‘not what things to know, but how to know them; how to make them into things to know’. This is evidently not a function the UKRI/REF system values.

so then,

To return to my initial ‘harshest case’, a few details: I undertook (on and off) a Bachelor of Arts in English at King’s College London from 2017–2022, and then a Master of Arts in Modern Literature and Culture, also at King’s, from 2022–2024. King’s was one of the two founding colleges of the University of London in 1836, and so is an example of an older university whose constitution has changed over time under marketising forces.

What passing through the UK university system in the 2020s feels like is an experience of uncanny co-inertia. Institutions and students are locked into a cemented producer-consumer dynamic of ‘knowledge-giver’ and ‘knowledge-ingester’. The institution must ensure that the thing it produces – the transferrable unit of ‘knowledge’ – is standardised, to ensure a predictably positive set of results vis-à-vis graduate employment rates, student satisfaction rates, REF/TEF scores, HEI table rankings, and therefore funding. A Humanities department, in this paradigm, gives rise to a strange dissonance between form and content. The subject matter of research and study is filled with apparently important topics/events: theories of history, evolution of ideologies, formal relationships between art and culture, geopolitical dynamics and interdisciplinary studies of cultural media (modules I’ve personally taken have ranged from ‘Afro-Asian Transcultural Memory: Text and Textile’, looking at novels pertaining to 20th-century migrations from India to South-East Africa and their associated clothing/fabric trades, to ‘Medieval Science Fiction’, examining how relationships to technology and the ‘other’ have influenced a science-fiction tradition traced back to 1000AD). But the formal structure of this study is regimented and invariable: attend [x] lectures per week, attend [y] seminars per week, complete [z] essays per module, per semester; attain [a] module credits, complete [b] exams over [c] preset examination periods per year. At the level of the essay, through trial and error (marker feedback), a student is disciplined into reproducing work in the exact style – tone, format, argumentative structure – demanded by the marking criteria. Repeatedly, at the staff panel held at the commencement of each academic year, the horizon of student imagination is demonstrated in the hot question on everybody’s lips: what is the exact ratio of secondary-source citation to word count?

I was walking through the gentrification project of Elephant and Castle with my partner the other day (the demolition of the central shopping centre, a local community hub, to make way for yet more University of the Arts London (UAL) buildings),59 and wondered aloud: ‘Are they really trying to produce more artists?’

Is producing artists the prerogative of UAL, or indeed the King’s A&Hs departments? Are market pressures – increasingly orienting institutions towards the provision of programmes that contribute to economic productivity – really concerned with the production of artists? Or is communicating to prospective students (primary sources of ‘income’) that this is the case, the institution’s only path to financial viability? Recall Browne: ‘There will be more investment available for the HEIs that are able to convince students that [their degrees are] worthwhile.’

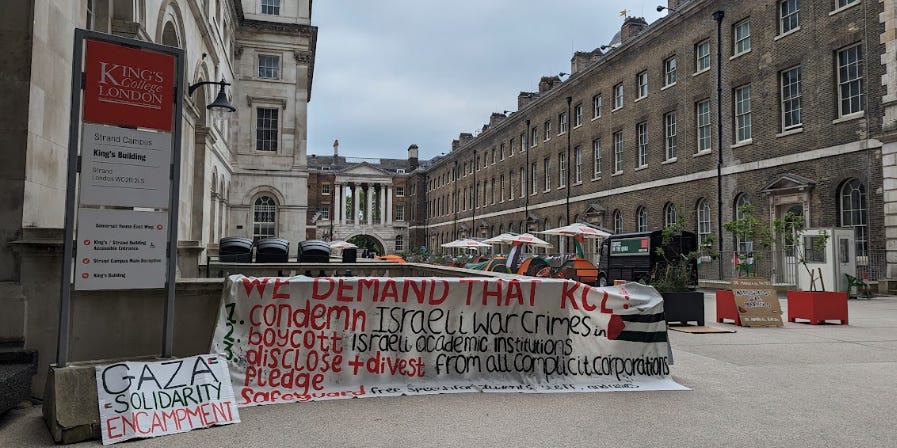

To return, finally, to Robbins and the MoR, is it any longer the prerogative of universities to produce ‘cultivated citizens’ who are ‘actively participating’ in their ‘community’? It has always seemed to me, in my experience, that the most active citizenship on display on university campuses is essentially against the grain; that citizenry can be observed on campus only in acts of extra-institutional acts of solidarity and community-building. Take, for one, the Palestine Solidarity encampments that swept the UK in the wake of the 2023- Israeli genocide, which, in the case of the King’s 2024 encampment,60 forced the administration’s hand into divesting from arms manufacturing companies – Lockheed Martin, L3Harris Technologies, Boeing – that were supplying arms to the IDF.61

Or another, the climate-action strike at University of Brighton,62 which can be seen echoing in a series of 2023 climate student protests across Europe:63

The first action of this kind I can remember seeing, organically and unexpectedly, was during a brief stint down at the University of Exeter, whereat hundreds of students gathered in indignation to mourn the shooting of a Hong Kongese 18-year-old pro-democracy protester at a CCP military parade:64

These acts of citizenship feel aberrational, rather than natural products of the university system.

The concerns of the university are the rankings, the excellency scores, the funding. At the level of the individual student, the world becomes the essay or exam mark. Recall Graeber: ‘“reality” – for the organisation – becomes that which exists on paper.’ The entire higher education sector feels like a decaying stalemate: two ‘zombies’ – the student-consumer and the corporate-managerial-university – each looking at each other through a pane of glass, unsure who’s here for whom, exactly, and why.

––

(03:23 – 03:35)

https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/parliament-and-the-first-world-war/legislation-and-acts-of-war/education-act-1918/

https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Geo6/7-8/31/enacted

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_universities_in_the_United_Kingdom_by_date_of_foundation

https://books.google.co.uk/books?id=0RBOAAAAMAAJ&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false

https://education-uk.org/documents/robbins/robbins1963.html

John Maynard Keynes, General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936; Palgrave Macmillan 2018), p.105

Karl Marx, Capital: Vol.1 (1867; Penguin Classics 1990), pp.342-343

(1:04:21 – 1:11:12)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bandung_Conference

Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth, trans. C. Farrington (1961; Penguin Classics 2001), p.76

Ilan Pappé & Noam Chomsky, On Palestine (Penguin 2015), pp.63-64

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1973_oil_crisis

https://history.state.gov/milestones/1969-1976/nixon-shock

https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/pound-in-your-pocket-devaluation-50-years-on/

https://www.nytimes.com/1972/06/24/archives/british-let-pound-float-in-value-in-world-market-de-facto.html

Marx, Capital: Vol.1, pp.162-163

https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/oil-shock-of-1973-74

https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/inflationandpriceindices/articles/consumerpriceinflationhistoricalestimatesandrecenttrendsuk/1950to2022#:~:text=Inflation%20began%20to%20steadily%20increase,including%20owner%20occupiers'%20housing%20costs

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1972_United_Kingdom_budget

https://www.gresham.ac.uk/watch-now/imf-crisis-1976#:~:text=In%201976%2C%20the%20Labour%20government,during%20a%20period%20of%20austerity. (22:04-)

Ibid, 23:56 – 27:28

Owen Jones, This Land: The Story of a Movement (Allen Lane 2020), p.15

George Monbiot and Peter Hutchison, The Invisible Doctrine: The Secret History of Neoliberalism (Penguin 2025), p.72

Ibid, p.23

Ha-Joon Chang, Economics: a User’s Guide (Pelican 2014), p.65

Ibid, p.66

https://www.education-uk.org/documents/jarratt1985/index.html#02

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Further_and_Higher_Education_Act_1992

https://education-uk.org/documents/dearing1997/dearing1997.html

https://www.education-uk.org/documents/acts/1998-teaching-and-higher-education-act.html

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Higher_Education_Act_2004

https://www.education-uk.org/documents/pdfs/2010-browne-report.pdf

https://www.brentwoodlibdems.org.uk/news/article/nick-clegg-confirms-commitment-to-scrapping-tuition-fees

https://www.theguardian.com/news/datablog/2010/dec/09/tuition-fees-higher-education

https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2012/sep/19/nick-clegg-apologies-tuition-fees-pledge

https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-10155/#:~:text=The%202010%20Browne%20report%20advocated,of%20more%20than%20%C2%A36%2C000.

https://www.hepi.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/Clean-copy-of-SNC-paper1.pdf

https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/media/upycgog5/ofs-2025_26_1.pdf

Jarratt Report, pp.14-15

https://www.officeforstudents.org.uk/publications/annual-review-2023/a-statistical-overview-of-higher-education-in-england/

OfS 2025, p.26

Roger Brown, ‘The Marketisation of Higher Education: Issues and Ironies’, New Vistas Vol.1 (2014), p.7

Cris Shore and Susan Wright, ‘Privatising the Public University: Key Trends, Countertrends and Alternatives’, in Death of the Public University? Uncertain Futures for Higher Education in the Knowledge Economy (2019) 1-28 (p.4)

David Graeber, Bullshit Jobs (2018), p.47

https://www.historyworkshop.org.uk/education/a-decade-of-crisis/

https://www.theguardian.com/education/2014/oct/12/have-universities-been-privatised-by-stealth

https://www.theguardian.com/money/article/2024/aug/29/uk-graduates-struggle-job-market

https://explore-education-statistics.service.gov.uk/find-statistics/student-loan-forecasts-for-england/2024-25

Shore and Wright, p.10

Monbiot and Hutchison, pp.21-22

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/education-11627843

https://www.ukri.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/UKRI-241023-BudgetAllocationExplainer2022To2025.pdf

https://studyinternational.com/news/research-excellence-framework-ranking-humanities/

https://www.theguardian.com/education/2018/dec/05/our-research-funding-system-is-shortchanging-the-humanities

(05:55-)

https://corporatewatch.org/elephant-castle-shopping-centre-the-battle-at-londons-gentrification-ground-zero/

https://roarnews.co.uk/2024/breaking-pro-palestine-encampment-protests-launch-at-kings-college-london/

https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/kings-college-halt-direct-investments-israels-arms-suppliers

https://www.theguardian.com/education/2019/sep/19/campus-is-the-perfect-place-to-disrupt-why-university-students-are

https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/may/05/students-occupy-schools-universities-europe-climate-protest#:~:text=Students%20occupy%20schools%20and%20universities%20across%20Europe%20in%20climate%20protest&text=In%20the%20UK%20occupations%20were%20under%20way%20at%20the%20universities%20of

https://archive.thetab.com/uk/exeter/2019/10/01/hundreds-gather-outside-forum-protesting-against-situation-in-hong-kong-43127

astounded by all of the research u put into this 💚 incredible work, as always.

Great to see new minds tackling the dystopian horror genre so head on.